Climbing My Family Tree

In Climbing My Family Tree I share stories of my ancestors as I discover them, so the posts are sporadic. My family history is a work in progress, and I might have to backtrack occasionally if (when) I make mistakes, so if we share a branch or two I encourage you to double check the research sources rather than accepting mine wholesale. I hope you enjoy reading my posts and will visit often to find new posts. I enjoy sharing them with you!

Friday, April 26, 2024

Esther Kersey (1783-1850) and Abraham Wolfington (1775-1850), early Indiana pioneers and my fifth great grandparents

Sunday, January 2, 2022

Eleazar Kersey (1762-1816) and Elizabeth Harlan Kersey (1762-1845), Quakers, my 5th great grandparents

|

| Guilford County North Carolina Image by David Benbennick, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. (Click to make bigger.) |

In my last post, I wrote about Elizabeth

Harlan’s father, Stephen Harlan (1740-1830), and the family trek from Chester

County Pennsylvania to the frontier regions of North Carolina, that story can

be found HERE.

Elizabeth Harlan, the oldest daughter of

Stephen Harlan and Mary Carter (1740-1824) was born in Chester County

Pennsylvania in 1762. She was the oldest of at least nine children: Elizabeth (bn.

1762, dd. 27 Feb 1845, m. Eleazar Kersey 1784),

Alice Ellen (bn 22 July 1764, dd 17 June 1835, m. Moses Robbins 1786), Margaret

(7 Dec 1766, dd 30 Nov 1825, m Obed Barnard 1810), Stephen (bn. 25 Jan 1773, dd.

6 July 1859, m. Alice Smith 1795), Edith (bn. 6 Sept, dd. 27 March 1847, m.

William Hill), Enoch (bn. 17 March 1776, dd. 9 June 1863, m. Abigail Jones

1805), Mary (bn. 12 Sept 1779, dd. 22 May 1841, m. William Morrison 1802), and

Ruth (bn. ?, dd. ?, m. George Criscow 1814), Ann (bn. ?, dd. 1866).

Elizabeth would

have been approximately three years old when her family migrated from the

Pennsylvania colony to North Carolina. They initially moved to Cumberland

County, NC and by 1769, when she was seven, had moved to a more frontier area

of North Carolina in Guilford County that later was sectioned off to become

part of Randolph County. Her father was

a farmer, millwright, and wagon maker. The post about her father is HERE.

|

| (Click to make bigger.) |

In the years

just prior to the American Revolution Quakerism in North Carolina experienced

its second great wave of migration and growth, and by the 1770’s, the greatest

concentration was in the Piedmont region where the Harlans moved to.

Eventually, there were twenty-three Quaker monthly meetings in North Carolina,

each composed of representatives from several individual meeting houses, who

sent delegations to two Quarterly Meetings in the eastern and western parts of

the colony. A Yearly Meeting of North Carolina Friends (eventually held at the

New Garden Meetinghouse) met and maintained contact with Yearly Meetings in

Philadelphia and London.

After the Harlan

family moved to Guilford County, Elizabeth met and subsequently married Eleazar

Kersey, whose family had come to North Carolina about 15 years before the

Harlans. Eleazar was born the same year as Elizabeth, on 27 August 1762, in

Springfield, Guilford County, North Carolina. He was the fifth son born to his

parents, William Kersey (1722-1764) and Hannah Hunt (1730-?), and his father’s

sixth son. Eleazar’s father, William, had first married a woman named Elizabeth

(?-1749) and had one child, also named William Kersey (bn. 15 Nov 1745 -?),

likely in PA or VA, and subsequently married Eleazar’s mother, Hannah Hunt in Loudoun

VA, outside of Meeting. William and Hannah’s children, all born in Guilford

County, NC, were: Amos Kersey (bn. 15 Feb 1751, dd. 7 July 1831, m. Dinah

Beeson 29 Mar 1786, & m. Elizabeth Willson 17 April 1794), Jesse Kersey (bn.

1 Dec 1753 dd. 7 Nov 1822, m. Rachael Haworth 1805), Daniel Kersey (6 Nov 1757,

dd. ?, m. Mary Carter 25 Novr 1778, m. Ann Irwin 16 Oct 1800), Thomas Kersey (bn.

15 Sept 1759, dd.10 Aug 1835, m. Rebecca Carter 1782) and Eleazar Kersey (bn.15

Aug 1762, dd. 1 June 1816), my fifth great grandfather. Tragically, Eleazar’s

father died two years after Eleazar was born.

|

| (Click to make bigger.) |

When Eleazar and

Elizabeth were fourteen, the American Revolution began. Many Americans today

don’t realize that the revolution took place over five years, 1776-1781.

After the

Regulator's War (See entry on Elizabeth’s father, Stephen Harlan, for an

explanation of the Regulators War,) when it became apparent that such conflicts were not over

and would eventually result in greater bloodshed, the North Carolina Yearly

Meeting convened on October 27, 1775, to issue an epistle which set forth the

position of North Carolina Friends with regard to any future political

contests. The epistle defined the principles which governed North Carolina

Quakers throughout the revolutionary years. Reiterating their opposition to war

yet avowing their allegiance to the Crown and insisting that many engaged in

the dispute with England were “Honest and Upright”. It also spoke of all

"Plottings, Conspiracies, and Insurrections” as works of Darkness"

and reminded Friends of advice from the London and Philadelphia Yearly Meetings

"not to interfere, meddle or concern in these party affairs".

Quaker religious

principles forbade them from condoning the overthrow of any established

government; and required obedience to the existing government, when such

obedience did not run counter to conscience was a fundamental duty. To the

revolutionary forces this seemed to place the Quakers in the Loyalist camp. On

the other hand, since the Friends would not directly help the Crown, to the

British authorities, they seemed to be in sympathy with the rebels. The Quakers

themselves wanted to be left out of all of it, to remain peacefully in their

homes and to be neutrals in the conflict they saw coming. North Carolina

Quakers would not bear arms, pay muster or "draughting" (drafting) fees,

or hire substitute soldiers, pay taxes to a government which might support its military

operations, or hold office under it. Friends also declined to vote for delegates

to the state constitutional convention in 1776 and debated over the use of

paper money issued by the revolutionary government, eventually deciding to

leave that to each individual Quaker’s own conscience.

It was not easy

being neutral. The

Friends could not resist confiscations of their property for nonpayment of

taxes and fines by either the Crown or the revolutionary government. Friends also

had their lives threatened and/or were beaten by both sides for refusing to

join the local Crown or Patriot militias. Additionally, their lands were often plundered

by military forces on both sides of the conflict. Quaker homes, barns, and

pastures were repeatedly destroyed as armies moved through the lands; their horses

were taken for army mounts and their cattle and sheep for food for the armies

and fences were dismantled to be used as firewood.

As much as they

tried to stay out of the conflict, the war brought the conflict to their door

in 1781, with the

battles of New Garden, Guilford Courthouse, and Lindley's Mill. On March 15, in

the early morning hours, Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis sent off his

baggage under the escort of Lieutenant Colonel John Hamilton’s Royal North

Carolina Regiment, 20 dragoons, and Bryan’s North Carolina Volunteers, to

Bell’s Mill and marched with his army to attack Major General Nathanael Greene

at Guilford Court House. Greene had placed troops out in advance positions to

the south and west to give him fair warning of any potential attack. When the front line of the British army,

led by Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, encountered Lt. Col. “Light Horse” Harry

Lee’s troops just north of the New Garden meeting house, British and American

soldiers crashed into each other in the narrow lane. After the initial clash,

the British cavalry were pushed back, across what is now the Guilford College

campus to the New Garden meeting house where they were joined by infantry

units. The two sides exchanged fire twice more before American forces retired

north towards Greene’s army. The entire clash took over three hours and involved

617 Americans and 842 British (including American Tories and Hessians).

About thirty British were killed and more injured.

Several hours later the same day, British and

American forces met again at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse in the streets

in front of Quaker houses. This battle has been called "the largest and

most hotly contested action" in the American Revolution's southern theater

and involved a 2,100-man British force under the command of Lieutenant General

Charles Cornwallis and 4,500 Americans under Major General Nathanael Greene.

After a brutal battle, Cornwallis defeated the Americans but lost approximately

25% of his forces in the process and was in no position to pursue Greene.

Cornwallis decided to withdraw to his supply base in Virginia to rest and

refit.

After the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, there were hundreds of wounded

American and British soldiers. Cornwallis left his wounded at the New Garden

community under the care of the Quakers. When General Greene learned of

the Quakers’ generosity, he wrote a letter to the Friends requesting they

provide “relief of the suffering wounded at Guilford Court

House.” The Meeting responded that they would “do all that lies in

[their] power” to assist the wounded, despite the recent theft of resources by

both British and American soldiers. The New Garden Friends cared for 250

wounded British and American soldiers in the Meeting House. They were cared for in

an old two-story log house at the corner of New Garden and Ballinger Roads, and

at New Garden Meeting House, and in nearby Quaker homes. Of those who did not survive their

care, British soldiers were buried under an old oak tree in the New

Garden meeting 's graveyard with the bodies of the American dead buried beside

them.

Reproduction of a Philadelphia Broadside 1781, In the Emmet Collection, New York Public Library. (Click to make bigger.)

I don’t know whether Eleazar and Elizabeth were involved in the nursing of the soldiers but Eleazar lived in that area at the time so it is likely he helped especially as members of his mother’s family are referenced as assisting with the wounded in several history articles and books.

The first record

I have on Eleazar, after his birth, is his marriage to Elizabeth Harlan on 12

July 1784. Like her parents before her, Eleazar and Elizabeth went outside the

Quaker meeting to get married. On for October 1784, the meeting records for the

Deep River Monthly Meeting in Guilford County North Carolina, state “also

complains of Eleazar Kersey for going out in marriage; therefore this meeting

disowns the said Eleazar Kersey to be a member of our society until he condemn

his misconduct to the satisfaction of Friends William Tomlinson is appointed to

inform him of the proceedings of this meeting against him with his right of

appeal, and that he may have a copy of this minute by applying to the clerk.”

Eleazar and

Elizabeth’s daughter, Esther, was born in about 1784, and may have been the

reason the couple did not wish to go through the multiple monthly Meetings

involved in a Quaker marriage procedure (I described the marriage procedure in

this post on Ezekial Harlan). Their daughter Ayles (Alice) was born on 6 April 1785, in

Springfield in Guilford County North Carolina. It was some years before Eleazar

requested readmittance to the meeting, fitting the pattern I learned of while

researching for the post on Stephan Harlan, where oftentimes a couple who had

married outside of the Society would seek readmission just prior to requesting

a certificate of transfer to move to a new meeting.

Eleazar was

doing well as a landowner and farmer. On 16 May 1787, a survey was performed on

his land. It shows he owned 450 acres, on both sides of Richland Creek. The

survey document was recorded (perhaps recorded again) on 30 November 1796.

|

| 1st page of survey of Eleazar's land. (Click to make bigger.) |

Eleazar and

Elizabeth’s son Stephen Kersey was born on 6 May 1789, and their son Jesse

Kersey was born in about 1790. According to the 1790 census, the family lived

in Guilford County, North Carolina. The census counted 1 free white person male

under 16, 1 free white person male over 16 and 3 free white persons female in

the household. They had another son, William Kersey, in about 1791 and a fourth

son, Enoch Kersey, on 10 May 1794, also in Guilford County.

Now that he had

a family, Eleazar, who was now 31, wanted to start attending Monthly Meetings. On

4 August 1794, the minutes for the Deep River Monthly Meeting, stated that

“Eleazar Kersey appeared at this meeting and offered a paper condemning his

accomplishing his marriage contrary to discipline, which was accepted.” And

then, one month later, on 1 September 1794, the meeting minutes record, “Also

informs that Eleazar Kersey requests a certificate to Springfield Monthly

Meeting; David Sanders and Amos Mills are appointed to make the needful Enquiry

and if they find nothing to hinder, to prepare one and produced to the next

meeting.” A certificate of removal was prepared by the Deep River Monthly

Meeting on 6 October 1794. On the same date, the minutes of the Springfield

Monthly Meeting record, “Eleazar Kersey produced a certificate to this meeting

from deep River monthly meeting dated the 6th of 10 mo 1794, which was accepted.”

The Springfield Monthly Meeting was about 18 miles from the New Garden Meeting and

both were in Guilford County.

Map shows the Quaker Meeting Houses ("mh") in the county and where Richland Creek is (look bottom left area) (Click to make bigger.)

On 30 November

1796, Eleazar expanded his land by buying 129 acres by Richland Creek from

Arthur Carney, for 60 pounds. Two years later, Eleazar and Elizabeth’s next son

was born on 15 July 1798 and named after his father, Eleazar.

On 5 September

1801, the Springfield monthly meeting minutes stated that “the preparative

meeting informs this that Eleazar Kersey requests to have his children joined

in membership, and they have been under the care of the preparative, this

meeting grants the request. Their names are Stephen, William, Enoch, Jesse,

Eleazar & Moses.” A month later, on 3 October 1801, the Springfield Women’s

Monthly Meeting minutes, reflected that “Elizabeth Kersey requests for her two

daughters, Ayles & Esther, to be joined in membership & they having

been under the care of the preparative meeting some time, this meeting grants

for request.”

Another daughter

was added to the family when Elizabeth was born on 19 Jan 1805. Their last child, Moses, was born on 6

September 1806. Eleazar and Elizabeth were 44 when their last child was born.

The next record

I have for Eleazar is on 9 September 1815 when he was appointed to represent the

Springfield Monthly Meeting and attend the coming yearly meeting. Later that

year, on 4 November 1815, the minutes of the New Garden Quarterly Meeting, a

regional governing body above the local monthly meetings, show that “Elazar

Kersey” produced a certificate from the Springfield monthly meeting to the New

Garden quarterly meeting recommending him to the station of Elder, which was

accepted. This shows that Eleazar was a respected leader within his community.

He was 53.

Unfortunately,

tragedy struck the next year and on May 29, 1816, Eleazar wrote a short will,

just before dying on June 1, 1816. The will was probated in August 1816. It

read: “Be it remembered this 29th day of this fifth month in the

year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred & sixteen that I Eleazar Kersey

of Guilford County in the state of North Carolina being sick and weak in body

but of sound mind & of majority make this my last will & Testament in

the following manner it is my will that all my just debts and funeral charges

should be first paid and discharged by my executors hereinafter named. Item I

give & bequeath unto my loving wife Elizabeth Kersey all my movable effects

except what is hereafter in this will directed to be given to my children and

when she has done with it let my daughter Elizabeth Kersey have what remains

thereof And let my wife have full privilege of living in my dwelling house

during her widowhood, also her maintenance.

Item I give

& bequeath unto my two sons Stephen & William Kersey all that piece of

land which I bought of William Beals to be equally in value divided between

them at the direction of my executor to be theirs, their heirs or assigns

forever Item it is my wish that my said

two sons Stephen & William should pay cash of [?] $25 to my executors to

help pay my debts – Item I give & bequeath unto my four sons Enoch Jesse

Eleazar & Moses Kersey all that piece of land whereon I now live to be

equally (in value) divided among them at the discretion of my executors to be

theirs their heirs or assigns forever – – is my will that Eleazar my son should

have thy dwelling house when his mother has done with it. Item I give and

bequeath unto my son Enoch that mare his but if she has a cold let his brother

Eleazar have the first she brings forth Item I give I give & bequeath unto

my two sons Jesse & Moses each of them a colt which has been called theirs.

Item I give & bequeath unto my daughter Elizabeth Kersey one feather &

and furniture bed one desk and one large pewter disk. Item. I give &

bequeath unto my two daughters, Alice Beeson & Esther Wolfington to each of

them five shillings sterling And lastly I nominate and appoint my trustee

brother in law, Stephen Harlan, & my wife Elizabeth Kersey & my son

Stephen Kersey executors of my last will and testament thereby making void all

former wills by me before made or appearing in my name declaring allowing or

confessing item as no other to be my last will & testament.” … The will was

signed by Eleazar Kersey and witnessed by Amos Kersey, William Kersey, and

Elizabeth Kersey, likely two of his sons and his wife.

|

| Eleazar Kersey's Will. (Click to make bigger.) |

His wife,

Elizabeth survived him. I’ve found no record of Elizabeth remarrying after

Eleazar died even though she survived him by twenty-nine years. She lived to

see three of her children migrate 500 miles away to Indiana, and to see at

least three of her other children predecease her (I don’t know when two of her

children died). Elizabeth died on 27 Feb

1845.

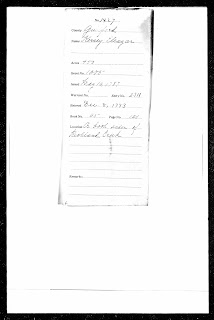

Death record for Elizabeth Harlan Kersey from the minutes of the Springfield Monthly Meeting.

(Click to make bigger.)

Eleazar and

Elizabeth’s children were: my fourth great grandmother, Esther Kersey (bn.

about 1784, dd. about 1850, m. Abraham

Wolfington), Ayles (Alice) Kersey (bn. 6 April 1785, dd. 10 April 1850, m. Seth

Beeson 18 Oct 1804), Stephen Kersey (bn. 6 May 1789, dd. 12 march 1845, m.

Jemima Leonard in 1812), Jesse Kersey (bn. about 1790, dd. ?), William Kersey (bn.

about 1791, dd. 3 Feb 1840), Enoch Kersey (bn. 10 May 1794, dd. 1 Dec 1837, m.

Sarah Curl 6 August 1834), Eleazar Kersey (bn. 15 July 1798, dd. 8 March 1854,

m. Naomi Hodson, 21 November 1835), Elizabeth Kersey (bn. 19 Jan 1805, dd. ?),

and Moses Kersey (6 Sept 1806, dd. Nov 1841, m. Asenith Ricks 24 October 1833).

History and Genealogy of the

Harland Family in America, and particularly of the descendants of George and

Michael Harlan, who settled in Chester County PA, 1687, compiled by Alpheus

Harlan (The Lord Baltimore Press 1914); Swarthmore College; Swarthmore,

Pennsylvania; Minutes, 1746-1768; Collection: Philadelphia Yearly Meeting

Minutes; Call Number: MR-Ph 339, U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935,

Ancestry.com; North Carolina, Land Grant Files, 1693-1960,

Ancestry.com; North Carolina Quakers in the Era of the

American Revolution by Steven Jay White, University of Tennessee –

Knoxville https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2514&context=utk_gradthes; Quakers

at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse - Guilford Courthouse National Military

Park (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov); Battle of New Garden | American

Revolution Tour of N.C. (amrevnc.com); Battle

of New Garden Meetinghouse • American Revolutionary War; Copy of

sketch of New Garden Quaker community, Guilford Co., North Carolina, time of

battle of Guilford Court House, March 15, 1781 - Family Records - North

Carolina Digital Collections (ncdcr.gov); Quaker

Meeting House Site of Skirmish Prior to Guilford Courthouse | NC DNCR

(ncdcr.gov); New Garden Friends Meeting – The Christian People called

Quakers by Hiram H Hilty, first printed in 1983; revised and expanded 2001 (New

Garden Friends Meeting : the Christian people called Quakers (archive.org));

NC Land Grant Images and Data |

Home (nclandgrants.com); Wills, 1771-1943; Author: North Carolina. County

Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions (Guilford County); Probate Place: Guilford,

North Carolina, digitized by Ancestry.com; 1790 United States Federal Census

Monday, March 15, 2021

Stephen Harlan (1740-1830), Farmer, Millwright, Wagon-Maker, Friend

Stephen Harlan is my sixth great-grandfather. He is the son

of William Harlan (1702-1783) and Margaret Farlow (1703-1767) – I wrote about

them HERE.

This is another post where I’m locking

my perfectionism in the closet and proceeding anyway, in defiance of pandemic

brain exhaustion. (I don’t have much documentation on him and I couldn’t verify

as much of the family history as I’d prefer, but I learned a lot of history I

never knew before in researching him and there's a wonderful love story towards the end of the post). The “History and Genealogy of the

Harland Family in America”, compiled by Alpheus

Harlan describes Stephen as a farmer, millwright, wagon-maker, Friend. He is

also a pioneer. In my last post, I stated that in my research of the Harlan

line, I have found that the older sons tended to stay close to home their whole

lives and the younger ones tend to be the pioneers leaving and pushing further

into the new country. Stephen’s father, William, was the first-born son and lived

his whole life in the county in which he was born. On the other hand, Stephen

was their seventh child and fourth son, and he moved his family to the western frontier

counties of North Carolina (now mid-North Carolina), about 440 miles from his

parents’ home.

Stephen's parents, William and Margaret, had nine

children: Mary Harlan (bn 1722- dd ?, married William Moore 1742), William

Harlan (bn 1724- dd 1819, married Abigail Hollingsworth 1743), Jonathan Harlan

(bn 1726- dd 1774, married Elizabeth Webb 1749), Alice Harlan (bn 1730- dd

1797, married Richard Flower 1754), Sarah Harlan (bn 1732- dd 1775, married

Robert McMinn 1749), Stephen Harlan (bn 1740- dd 1830, married Mary

Carter abt 1761), George Harlan (bn 1743- dd 1821, married Elizabeth

Chandler 1768), and Enoch Harlan (bn 1745- dd 1794, married Edith Carter 1769). Stephen was born on 12 May 1740 (3, 12, 1740)*

in West Marlborough, Chester County, the British colony of Pennsylvania.

I have no information about

his childhood and growing up years. As I noted the post about his father, I

could find no records on the family between his parents’ marriage and his

mother’s death. All of the secondary sources and genealogy website posts about

Stephen Harlan that I have found have referred to him as a Quaker (Friend), but

actual Quaker records (or at least the ones I can access from home sitting on

my couch) are very sparse concerning Stephen. He probably was Quaker since his

parents were and some of the later Quaker meeting records of his children in

North Carolina indicate that they were birthright Quakers.

It is perhaps ironic that

the one Quaker record I found regarding Stephen is a meeting record for the New

Garden Meeting in Pennsylvania: “given forth at our mo. Meeting of Newgarden

held the 28 day of the 4th mo 1759 -- Whereas Stephen Harlan son of

William Harlan have had his education amongst us, but he not regarding the

Principles Councils nor Precautions, but being Strong in his own self will,

Placed his Affection on a woman not of Our Society & was Marryed by a

Priest for which disorderly and Stubborn practice we disown him to be of our

Society until by Repentance he comes to see the Evil of his ways, which is our

desire he may. Signed in & on behalf of the Meeting by Isaac Jackson.”

|

| New Garden Monthly Meeting 30 Jun 1759, Stephen Harlan, Disowned Quaker Meeting Records, Ancestry.com |

All the secondary sources I

have found agree that he was disowned by the Society for marrying his wife,

Mary Carter, daughter of Nathaniel and Ann (McPherson) Carter, farmers, in the

Immanuel (Episcopal) Church in Newcastle in the Delaware colony, but they all

have the marriage occurring on 2 December 1761 – over two years later. I

haven’t found a disowning record for him in 1761 or 1762. That’s not to say it

doesn’t exist, but I didn’t find it (yet). If Stephen and Mary married in 1759,

they were both 18; if they married in 1761, they were both 21.

He would not necessarily

have remained disowned. Members could be disowned for a variety of reasons

(marrying outside of the society, getting drunk, dancing, not dressing plain, fighting, playing

cards, joining the army during a war, etc.) and

could be readmitted to the Society of Friends if they submitted a written

petition to the Meeting acknowledging and repenting of their

wrongdoing/willfulness and then the Meeting would decide whether to readmit

them to the Society.

In going outside the meeting

to marry, Stephen followed in the footsteps of his new father-in-law, Nathaniel

Carter, who was a birthright member of the Society of Friends, but married Ann

McPherson in an Episcopal ceremony at Holy Trinity (Old Swedes) Church in

Wilmington, Delaware. So, his new in-laws were likely not quite as shocked as

his own parents would have been.

A Quaker marriage took

months (see this post for a description of the marriage process). Some couples did not want to wait

that long and would go “outside of the Meeting” to be married by another

religion’s church leader or by a judge. Often a couple who had married outside

of the Society would seek readmission just prior to requesting a certificate of

transfer in order to move to a new meeting. If this occurred years after their

marriage any children born prior to their readmission would not have their

births recorded in the monthly meeting records. I have been unable to find

contemporaneous birth records on any of Stephen and Mary’s children in the

Quaker records (several of them do have their birthdates recited in later Quaker

records when they married or died). I don’t know whether that is because

Stephen and Mary never were readmitted or because the area the family later

moved to was a frontier area with a Meeting that was subsequently “laid down”

(closed) in 1772, and the records for that Meeting have been lost.

Stephen and Mary had at

least nine children: Elizabeth (bn 1762, dd 27 Feb 1845, m. Eleazar

Kersey 1784), Alice Ellen (bn 22 July 1764, dd 17 June 1835, m. Moses

Robbins 1786), Margaret (7 Dec 1766, dd 30 Nov 1825, m Obed Barnard 1810), Stephen

(bn 25 Jan 1773, dd 6 July 1859, m. Alice Smith 1795), Edith (bn 6 Sept, dd 27

March 1847, m. William Hill), Enoch (bn 17 March 1776, dd 9 June 1863, m.

Abigail Jones 1805), Mary (bn 12 Sept 1779, dd 22 May 1841, m. William Morrison

1802), and Ruth (bn ?, dd ?, m. George Criscow 1814), Ann (bn ?, dd 1866).

By the time Stephen and Mary

married, the eastern portion of Pennsylvania was becoming quite crowded and it

was difficult for a younger person to find land to farm. The proprietors of the

colony discouraged expansion West into the mountains because of treaties with

the indigenous tribes so expansion had been deflected southward into the

valleys of Maryland and Virginia, and into the Piedmont region of the Carolinas.

Within a few years after their marriage, Stephen and Mary and their first two

children joined what has been described as “the first large overland migration

of families in American history”, to the South. The “History and Genealogy of the Harland Family in America…”

states that they may have moved south to Cumberland County NC with Mary’s

family and I’ve seen other blogs writing that they joined Mary’s family

who were already in Cumberland County, NC.

At that time Cumberland Country was part of the North Carolina

backcountry – now, it is towards the eastern edge of the middle of the state.

The trip from Southeast

Pennsylvania to the North Carolina backcountry was over 400 miles long. The

migrating families largely followed one of two routes South. But before leaving

they had to plan their journey and pack their belongings, paring down what they

owned, so that it all fit in a Conestoga wagon, and selling or giving away the

rest. The Harlans likely had the advantage of knowing quite a bit about the

destination from correspondence with Quakers who had moved to the area before

them. Also, in many cases, fathers made a preliminary trip to the backcountry

to see what prospects there were and what the trip would be like before taking

the family there, and it is possible that Stephen made that trip on behalf of

his family. It would help explain the extended gap between children after the

oldest two were born.

Conestoga Painting (1883) by Newbold Hough Trotter

in the public domain

Most families did not have a wagon before the trip and had to buy one, and the wagon of choice for the trip, the Conestoga wagon, was developed in Lancaster County Pennsylvania. It is possible that since Stephen Harlan has been described as a wagon maker, he may have built one or more for the family for the trip. It was the primary overland cargo vehicle until the railroads were invented. Because of its weight, it required a team of at least four horses. They would pack the wagon with clothing, food for at least for a few days and a similar amount of feed for the animals traveling with them, and a canvas tarp for a tent, and items they would need in their new homes such as tools, farming implements, cloth for clothing, and seed.

The main route was a series of roads and paths on a north-south course that came to be called the Great Wagon Road, where travelers left from Philadelphia, crossed over the gentle hills of Chester and Lancaster counties towards South Mountain (part of the northern extension of the Blue Ridge Mountain range) crossing the Susquehanna River by ferry or by ford, through the Maryland Hill country, into Virginia, where they had to cross the Potomac River, by ferry or ford, usually above Alexandria. They would then travel on through the valley of Virginia heading towards Western North Carolina or Southwest Virginia, almost all of it uphill through oak and pine forest, rising from 2000 feet above sea level at the start to 3000 feet above sea level at the end. By 1753, the Great Wagon Road made up a significant chunk of the route that many took to the backcountry of Virginia North Carolina, with a spur called the Carolina Road. Families traveling on this route dealt with daily challenges. Traveling the back country roads with a party on horseback, or walking, with wagons full of supplies was difficult as they were poorly maintained and poorly marked, even by 18th-century standards; and at the end of the day, families had to set up camp or find shelter in a private home that was willing to take in travelers. There were inns/taverns along the way called Ordinaries, but quality varied significantly and families sometimes preferred to camp near the Ordinary rather than to pay for rooms. The Ordinaries also offered opportunities for the travelers to buy provisions, send mail ahead to their new community or back to the family they had left behind, and get directions for the next leg of their journey. It took about four to five weeks for a family to migrate from Pennsylvania to the Piedmont of North Carolina.

|

| Great Wagon Road and Carolina Spur Click to make bigger |

|

| 18th C East Coast Chesapeake Ferry Route PA to NC |

There was another route that was used by many from southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and northeastern Maryland. For people in those areas, the most direct route to the North Carolina backcountry was a trip along the length of the peninsula comprising Delaware and the eastern shores of Maryland and Virginia. The roads along this route were not any worse than the roads comprising the Great Wagon Road but traffic along this route was lighter than on other routes. One deterrent could have been the 60-mile ferry ride across the Chesapeake Bay from Cheristone in Northampton County to the town of Norfolk Virginia, as it involved a significant investment of money and time. The ferry ran across the bay on a schedule determined by tides and winds, and those waiting to take it could be delayed for several days, and if enough people arrived waiting for the ferry, there would be no guarantee of there being sufficient room on the ferry for all those who waited. The roads beyond the ferry were often just paths instead of actual roads, and directions were confusing. There were also Ordinaries along this route, providing the same services as was available on the Great Wagon Road, and again many families preferred to camp with their Conestoga’s near the Ordinaries and save the money for settling in their new homes. Travelers could buy provisions from private homeowners along the way and occasionally stay the night with a breakfast provided in the morning. It was a long, hard trip with a family and it took approximately three weeks if there was no hold up at the Chesapeake Bay ferry.

|

| Map of North Carolina Counties in 1760 |

It’s estimated that Stephen and his family made the trip in 1765, so that means the children on the trip would have been Elizabeth, 3, and Alice, approximately 1-year-old. The family first moved to Cumberland County, which today is not part of the Piedmont region (the county has shrunk as other counties were formed out of the original western parts of the county and it is now wholly in the eastern region of the state). Since they moved to Cumberland County, if they did rejoin the Quaker meeting, they would have joined the Dunn’s Creek monthly meeting in the Cape Fear River Valley (the Meeting site today would be about 8 miles southeast of Fayetteville NC). In later years the Meeting closed, which may explain why there are no records from the Dunn’s Creek Meeting. As far as I can tell, Stephen and Mary did not have any children for the first several years after they moved to North Carolina. That may have been because of the effort put in to settle in a new area on the edge of civilization, and it also may have been because people tend to not want to have children during a period of disturbance or war, and they had moved into an area that was anything but settled politically.

In 1766, local conflicts had erupted when backcountry farmers and small merchants in the Piedmont, calling themselves Regulators, tried to fight government corruption, unclear land laws, problems in the court system, and taxes to help build a governor's palace in the Coastal Plain at New Bern. (Lord John Earl Granville, who had been rewarded with nearly one-half of North Carolina by the King for his services, admitted fees and taxes were excessive and that 50 percent of the taxes collected were embezzled by his agents.) The popular movement to eliminate this corrupt system of government and replace it with a fairer version came to be known as the Regulator Uprising, War of the Regulation, or the Regulator War. At first, 1765 through the spring of 1768, it involved sporadic local protests and clashes over attempts to collect taxes. In 1768, the clashes escalated and the local objectors came together in an organized opposition who called themselves the Regulation or Regulators. The Regulators acts became more violent (including invading the courts, driving judges from the bench and dragging and whipping attorneys through the streets) because they felt their efforts to object were being ignored. The movement climaxed with the Battle of Alamance on May 16, 1771. Colonial Governor Tryon led a well-trained loyal militia of about 1,000 men into the backcountry. The usual Regulator strategy was to scare the governor with a show of superior numbers in order to force him to give in to their demands, and depending on the account, the Regulators showed up with between 2000-6000 men. Governor Tryon ordered the Regulators to disperse and return to their homes and when they did not, he shot and killed one of the leading Regulators. More shots were exchanged, but the untrained Regulator resistance dissolved and it was all over in two hours with nine deaths for the governor's forces and about the same for the Regulators. Following the battle, Tryon's militia army traveled through Regulator territory, where he had Regulators and Regulator sympathizers sign loyalty oaths, destroyed the properties of the most active Regulators and had six of the Regulators hung for their part in the uprising. He also raised taxes to pay for his militia's defeat of the Regulators.

|

| Battle of Alamance Postcard circa 1905 1915 by artist J Steeple Davis in the public domain |

The Society of Friends in their official capacity condemned the Regulation movement to the fullest extent. The Quakers' religious principles did not allow them to condone the overthrow or challenge of any established government; obedience to the existing government, when such obedience did not run counter to conscience, was a fundamental duty. However, individual Quakers were known to have sympathized with the Regulators. Throughout the movement's years, 1766 to 1771, members were frequently disowned for doing anything associated with the movement. The Cane Creek Meeting disowned or had denials published by twenty-eight members on grounds ranging from “attending a disorderly meeting” and “joining a group refusing to pay taxes” to actually taking up arms. In 1771, eighteen men were disowned, sixteen of them two weeks after the Battle of Alamance. On the other hand, many Friends were forced to contribute to the war against their will by the colonial government to meet demands for provisions and equipment for the provincial forces fighting the Regulators.

Stephen and Mary and their family had moved to the portion of North Carolina most affected by the Regulator movement, at the start of the movement. I don’t know if they were involved or held to Quaker standards of noninvolvement. Either way, it would have been a tense time to live through. Stephen and his family lived in Cumberland County for several years because at least two of the children were born in Cumberland County, after the defeat of the Regulator movement: Stephen in 1773 and Edith in 1775.

|

| Click to make bigger |

|

| Click to make bigger |

As always, when any of my ancestors moved large distances from their home, I wonder whether they ever went back home for a visit. There were likely letters to the people back home, because several of the books and articles I read referred to frequent letters from those Quakers in North Carolina back to relatives in Pennsylvania who returned them letters. In addition, traveling proselytizing Quaker speakers would carry messages from one family to another as they traveled. I do know that at least one of Stephen’s brothers followed him to North Carolina, and followed in his footsteps in more ways than one.

Stephen’s younger brother Enoch had helped Stephen’s family and the Carter family on the trip down to North Carolina. After he returned home, he sent a letter to Mary’s younger sister Edith telling her that he was home safe. The History and Genealogy of the Harland family includes a transcription of a letter from Edith Carter to Enoch dated July 28, 1766:

Stephen and Enoch’s mother died in 1767, and three years later, the minutes for the New Garden monthly meeting on November 23, 1769, noted that “Enoch Harlan, son of William, went to North Carolina without a certificate and married out of the Society. A testimony prepared against him to be read at London Grove preparative meeting and then sent to North Carolina.” From the New Garden monthly meeting minutes for December 2, 1769, “Enoch Harlan was disowned.”

|

| July 6, 1776 New Garden Meeting minutes, receiving Enoch Harlan into Society of Friends again and resolving to recommend him to the Center Preparatory Meeting Quaker Records, Ancestry.com |

[

From the New Garden monthly meeting, July 6, 1776: “Enoch Harlan who was testified against by this meeting, in the year 1769, now residing in Guilford County North Carolina, having sent a request to be received again under care but not having sent any acknowledgment for his misconduct he was wrote to by direction of that meeting on that account and also to a Friend there requesting that he might be visited by them and an account of his disposition being sent to us and his acknowledgment being now received together with a few lines from Center Preparative Meeting in the said county signifying his orderly conduct of late, and their belief in his sincerity, both of which were read and the case solidly considered, and several Friends expressing their minds his offering is received, and Joshua Pusey is appointed to prepare a few lines recommending him to Center Monthly Meeting and bring it to the next meeting for approval." It was approved at the next meeting. With that certificate, Enoch was accepted back into the Society of Friends by the Meeting which had disowned him, and they recommended his admittance into the Center Monthly Meeting in North Carolina.

Enoch had married Edith Carter. The Harland history says that Enoch and Edith then moved to Randolph County, “where he rented and operated a sawmill and that he was a Cooper and a wagonmaker, and a good scholar for the day and was quite an astronomer” and he and Edith had at least 11 children. Since Stephen was described as a millwright in the family history, which was a specialist carpenter who designed, built, and maintained mills, including sawmills, I wonder whether he worked with his brother at the sawmill.

Stephen outlived his brother Enoch (dd 1794 of typhus) and many, if not all, of his other siblings; he also survived his wife Mary (dd 1824) and his daughter Margaret (dd 1825). Stephen died in 1830 in Randolph County, NC, USA, and was buried where his wife was buried in the Marlboro Friends Meeting Cemetery in Sophia NC. In his will, after directing that all his just debts be paid as quickly as possible after his death, he bequeathed one dollar ($1) each to his sons Stephen and Enoch and his daughters Elizabeth Kersey, Alice Robbins, Mary Morrison, and Edith Hill. He bequeathed to his daughter, Ruth Criscow his “featherbed and furniture thereto belonging.” He also bequeathed one dollar ($1) to his granddaughter Mary Bond, and he bequeathed to his grandson Stephen Criscow all his shop tools. Lastly, he stated that he wanted his daughter Ann Harlan to have his plantation [farm] during her natural life and that afterward, it was to return to his lawful heirs equally among them. He also left Ann all his household furniture (except the featherbed that went to Ruth).

|

| Will of Stephen Harlan, p.1 Click to make bigger |

|

| Will of Stephen Harlan, p.2 Click to make bigger |

x

*Note: Before 1752 England and its colonies used the Julian Calendar, in which the first day of the new year was March 25, and not the Gregorian Calendar (used today) in which the first day of the new year is January 1. While the Quakers followed the calendar commonly used by England, the Quakers designate months by numbers, such that in the Julian calendar First month (or 1st mo. or 1) was March. In writing dates in this essay that occur before 1752, I’ll state what the date would be in today’s calendar and then, in parentheses, I’ll include the date as I found it in the source used. [For a more in-depth explanation of the Julian calendar transition to the Gregorian calendar, and Quaker calendar see my post, Dating Induced Headaches for the Family Historian: Julian, Gregorian, and Quaker Calendars.]

History and Genealogy of the Harland Family in America, and particularly of the descendants of George and Michael Harlan, who settled in Chester County PA, 1687, compiled by Alpheus Harlan (The Lord Baltimore Press 1914); Swarthmore College; Swarthmore, Pennsylvania; Minutes, 1746-1768; Collection: Philadelphia Yearly Meeting Minutes; Call Number: MR-Ph 339, U.S., Quaker Meeting Records, 1681-1935, Ancestry.com; http://sites.rootsweb.com/~quakers/quakdefs.htm; PENNSYLVANIA AS AN EAELY DISTRIBUTING CENTER OF POPULATION By WAYLAND FULLER DUNAWAY, Ph.D. The Pennsylvania State College, pp. 134-169, file:///C:/Users/Jo/Downloads/28222-Article%20Text-28061-1-10-20121204.pdf; Southern routes: Family migration and the eighteenth-century southern backcountry Creston S. Long College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3202&context=etd; Dunn’s Creek Monthly Meeting, http://jamestownmeeting.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/ONCE-WE-WERE-FRIENDS-part-2.pdf; https://www.ncpedia.org/history/colonial/piedmont; North Carolina Quakers in the Era of the American Revolution by Steven Jay White, University of Tennessee – Knoxville https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2514&context=utk_gradthes; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_the_Regulation; https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/bassett95/summary.html; https://www.historyextra.com/period/georgian/who-regulator-movement-war-regulation-governor-tryon-battle-alamance-what-happened-outlander-real-history/; https://www.britannica.com/topic/Regulators-of-North-Carolina ; http://www.sonsofdewittcolony.org//mckstmerreg3.htm ; https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/nc_randolph_county_regiment.html; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millwright ; https://www.history.com/topics/westward-expansion/conestoga-wagon; Wills, 1663-1978; Estate Papers, 1781-1928 (Randolph County); Author: North Carolina. Division of Archives and History; Probate Place: Randolph, North Carolina, North Carolina, Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998, Ancestry.com