|

Salem Witch Hanging Engraving

Click to make bigger

|

When I was researching for the post on Joshua Currey, I came across a mention in a biographical article on one of his sons' wife’s brothers that said that one of the reasons that there were so many lawyers in the Estey family was because of the injustice done to his great-grandmother at Salem. …I did a double take, “Wait! Salem?!” So, of course, I had to do more research to see if that implied connection was accurate. It is! I’ve found the first ancestor I have actually read about in a history book prior to finding out I was related to her!

Mary Towne Easty (a/k/a Eastey/Esty/Estey/Eastick/Estie – consistent spelling was not important in earlier centuries) is one of my eighth great-grandmothers on my father‘s side. Hers is a tragic story, but very interesting.

She was born in Yarmouth, Norfolk, England to William Towne and Joanna Blessing Towne and was baptized on August 24, 1634. William Towne and Joanna Blessing were married on March 25, 1620, at the church of St. Nicholas in Yarmouth, England; Mary was the sixth of eight children and the last one born in England. William and Joanna’s children were Rebecca (1621-1692; m. Francis Nurse), John (1625-bef.1672, Susannah (1625 – bef. 1672), Edmund (1628-?; m. Mary Browning), Jacob (1632- ?), Mary (1634-1692; m. Isaac Easty), Sarah (abt. 1638 – abt. 1704; m1. Edmund Bridges, m2. Peter Cloyce) and Joseph (1639 - ?; m. Phoebe Perkins).

William and Joanna Towne came to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with their children, sometime between the years 1634, when Mary was baptized in England, and 1638 when their youngest daughter was born in Massachusetts. In 1640, William is on record in the town book of Salem as being granted "a little neck of Land right over against his house on the other side of the river." They first lived in Salem Village, and then in 1651, they moved to Topsfield, where William purchased land. Mary was 17 years old. They were considered a respectable family, with Goodman William Towne described as “a man of character, substance and social position.”

In 1656, Mary Towne (22) married Isaac Easty (29), a farmer and cooper (barrel maker) from Salem Village. He was born on 17 November 1627, in Freston, Suffolk, England and had come to Salem in 1636 with his parents when he was nine years old. Isaac and Mary had nine children: Isaac (1656-1714, m. Abigail Kimball, my seventh great-grandparents), Joseph (1657-?), Sarah (1660-?, m. Moses Gill), John (1662-?), Hannah (1667-1741; m. George Abbott), Benjamin (1669-?), Samuel 1672-?), Jacob 1674-?), Joshua (1678-bef. 1718; m. Abigail ?).

Isaac and Mary moved to Topsfield somewhere around 1660, and in 1661, he was one of the commoners appointed to share in the Topsfield common lands on the south side of the Ipswich River. Isaac was one of the selectmen of the town in 1680, 1682, 1686 and 1688. He was also selected to serve on juries in 1681, 1684 and 1685. The local church register for 1684 shows that Isaac Estey, wife, and family, were members in full communion.

In 1670, Mary Easty’s mother, Joanna Towne, was suddenly accused of witchcraft by the Gould family after she angered them when she twice testified on behalf of a Topsfield minister, Rev. Thomas Gilbert, who had been brought to court after accusations by Gould family on a charge of intemperance. She was never tried in court, but the family spread rumors that she was a witch. According to Rebecca Brooks, writing for the History of Massachusetts blog in the entry “Mary Easty: the Witch’s Daughter”, the Gould family were close friends with the Putnam family of Salem Village, who later became the most active accusers in the Salem witch trials, and the main accusers against Mary Easty and her sisters.

|

Salem Village Map, 1692

Click to make bigger |

There were several years worth of ongoing land disputes between the Putnams and the town of Topsfield, between 1636 and into the 1680s. In 1680, the town of Topsfield appointed a committee to sue for bounds (boundaries) in the Putnams' countersuit. The general court heard the claims of the two parties and decided in favor of Topsfield. Throughout this suit and others that followed, the names of How, Towne, Estey, Baker, and Wildes appear frequently, either as a committee representing Topsfield, or as witnesses before the court, while on the other side the Putnam name appeared. In 1686, Isaac Easty, his son Isaac, and John and Joseph Towne testified in court that they had seen Capt. John Putnam and his sons harvesting trees within the Topsfield boundary and on Topsfield’s men’s properties. The court decided in favor of the Topsfield men which only made the Putnams more bitter. The Putnams were described as "strong-willed men, of high temper and seemingly eager for controversy and even personal conflict", in the article Topsfield in the Witchcraft Delusion (The Historical Collections of the Topsfield Historical Society, 1908, p. 23, 25), and they resented the Townes and Eastys.

In early 1692 the witch hysteria broke out in the fits and accusations of young girls in the community, including Ann Putnam, perhaps caused by boredom, perhaps by illness, perhaps by anxiety, or perhaps something they ate (one theory is that rye grown in Salem may have been contaminated with a type of fungus found in LSD). As noted in Hunting for Witches by Francis Hill, only three of the girls lived with both natural parents, the others were orphaned or semi-orphaned. The girls, like everyone else in the Puritan community, lived in fear of sudden attack from the Indians, of disease, of harsh punishment for minor transgressions, of God’s wrath and eternal damnation. It is not surprising that the girls might be influenced by the resentments, fears, and hatred of their elders, and named as witches those whom their parents and guardians saw as enemies. Given the ongoing land disputes involving the Townes, it is unsurprising now that among the first people accused, in March 1692, were Mary’s sisters, Rebecca Nurse* and Sarah Cloyce; they were jailed within a month of being accused. During the witch hunt at least one Putnam family member signed 15 of the 21 recorded complaints that survive. Approximately 150 people were accused of witchcraft in all.

Throughout April 1692, 21 people were charged with witchcraft, and every complaint was signed by a Putnam, either Thomas or John. One of those so accused, Mary Towne Easty, was my eighth great-grandmother, who had been known as a pious and respectable woman. Mary Easty was likely also a victim of the resentment carried by the Putnams as a result of the boundary disputes in which a number of her Towne and Easty family members were involved. There may also have been resentment against the family because her husband was a large landowner and farmer, and was town selectmen for at least four years. It also did not help that she was known to be related to too many accused witches, between her mother and her sisters, for there not to be suspicion cast on her.

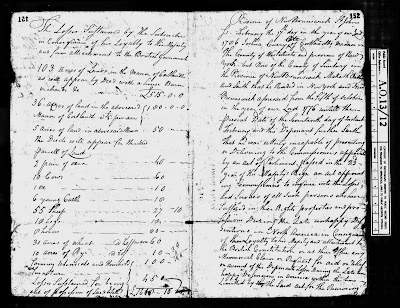

Mary Easty was arrested on April 21, 1692, and examined by magistrates John Hawthorne and Jonathan Corwin on the next day.

|

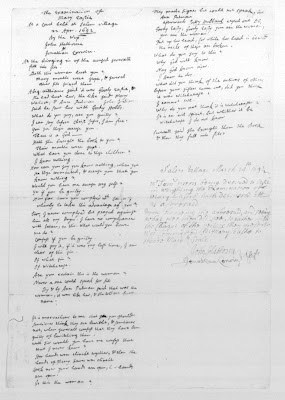

Notes of Examination of Mary Towne Easty, 1692

Click to make bigger |

Transcription of the examination notes, in the picture above. Portions in brackets are my additions, for clarity:

The Examination of Mary Eastie.

At a Court held at Salem village 22. Apr. 1692

By the Wop. [Worshipful] John Hathorne & Jonathan Corwin.

At the bringing in of the accused severall fell into fits.

[Magistrate to girls] Doth this woman hurt you?

Many mouths were stopt, & several other fits seized them

Abig [Abigail] Williams said it was Goody Eastie, & she had hurt her, the

like said Mary Walcot, & Ann Putman, John Indian said her saw her

with Goody Hobbs.

[Magistrate to Mary Easty] What do you say, are you guilty?

[Mary Easty] I can say before Christ Jesus, I am free.

[Magistrate] You see these accuse you.

There is a God --

[Magistrate to girls] Hath she brought the book to you?

Their mouths were stopt.

[Magistrate to Mary Easty]: What have you done to these children?

[Mary Easty]: I know nothing.

[Magistrate] How can you say you know nothing, when you see these tormented, & accuse you that you know nothing?

[Mary Easty] Would you have me accuse my self?

[Magistrate] Yes if you be guilty. How far have you complyed w'th Satan whereby he takes this

advantage ag't you?

[Mary Easty] Sir, I never complyed but prayed against him all my dayes, I have no complyance with Satan, in this. What would you have me do?

[Magistrate] Confess if you be guilty.

[Mary Easty] I will say it, if it was my last time, I am clear of this sin.

[Magistrate] Of what sin?

[Mary Easty] Of witchcraft.

[Magistrate to girls] Are you certain this is the woman?

They made signes but could not speak, By and by Ann Putman said that was the woman, it was like her and she told me her name.

[Magistrate to Mary Easty] It is marvailous to me that you should sometimes think they are bewitcht, & sometimes not, when severall confess that they have been guilty of bewitching them.

[Mary Easty] Well Sir would you have me confess that that I never knew?

Her {Mary’s] hands were clincht together, & then the hands of Mercy Lewis was clincht

Look now your hands are open, her hands are open.

[Magistrate to girls] Is this the woman?

They made signes but could not speak, but Ann Putman. Afterwards Betty Hubbard cryed out Oh. Goody Easty, Goody Easty you are the woman, you are the woman. Put up her head, for while her head is bowed the necks of these are broken.

[Magistrate to Mary Easty] What do you say to this?

[Mary Easty] Why God will know.

[Magistrate to Mary Easty] Nay God knows now.

[Mary Easty] I know He dos.

[Magistrate to Mary Easty] What did you think of the actions of others before your sisters came out, did you think it was Witchcraft?

[Mary Easty] I cannot tell.

[Magistrate] Why do you not think it is Witchcraft?

[Mary Easty] It is an evil spirit, but wither it be witchcraft I do not know.

Severall said she brought them the Book & then they fell into fits.

After examination, Mary was taken back to the Salem jail. It was very overcrowded in the jail and the conditions were terrible enough that four persons held in the jail, on witchcraft charges, died there. On May 18, Mary was released for reasons not recorded in the surviving records. However, one of her accusers, Mercy Lewis, continued to accuse Mary of sending her specter to torment her, and experienced extreme fits for a full day, claiming that Mary’s specter was threatening to kill her by midnight for her testimony. As a result, Mary was arrested again only 48 hours after she had been released based on a complaint made against her on May 20 by John Putnam, Jr. and Benjamin Hutchinson, on behalf of Mercy Lewis, Abigail Williams, and Mary Walcott. However, Mercy Lewis continued to have fits and severe convulsions all night, until the Salem magistrates were informed of the situation, and put Mary in irons, at which point the girl’s fits subsided. There is no remaining record of the examination pursuant to this arrest, but Mary Easty was indicted on two charges of witchcraft and first taken to the jail in Ipswich, then later moved to the jail in Boston.

The newly appointed Governor Phipps acted to try to control the hysteria by creating the Court of Oyer and Terminar (hear and determine) solely to hear witchcraft cases and appointing nine judges under a chief judge, the lieutenant governor. The Court of Oyer and Terminar allowed some weird evidence which we would never consider probative evidence today to be considered: the “touching test” (when the accused witches touched a girl during one of her fits and if the girl’s convulsions or fits stopped, then the accused was ruled guilty of witchcraft}; spectral evidence (testimony that a specter of the accused witches physically or mentally tormented the girls who were afflicted) and if one of the girls stated that the accused’s spirit was tormenting them, the court ruled the accused witch guilty of witchcraft; witch marks (the people of Salem believed the devil would find a teat, or mole, upon the accused body, and would suck the teat and leave blue and red marks on their body). Additionally, gossip, stories, and hearsay were treated as persuasive evidence. There was no presumption of innocence.

|

The Wonders of the Invisible World by Cotton Mather, 1693

Click to make bigger |

The jury in Mary’s sister Rebecca Nurse* case initially found her not guilty at trial, but when the girls heard the verdict they went into such fits, the jury was sent back to reconsider their decision, and then they convicted her. Rebecca was hanged in July 1692, along with four others similarly convicted.

Mary and Sarah were still being held in jail when their sister Rebecca was executed. Their families visited them regularly, even though the trip from Salem to Boston took more than half a day on horseback, and provided much support, but it had to be a terrifying time for the women, and for the families who had to know that the association with the women might also place them under suspicion. Prior to her trial, Mary Easty and her sister Sarah Cloyce jointly filed a petition, because they were “neither able to plead our owne cause, nor is councell allowed.” In the petition, they asked the magistrates to act as their legal counsel; requested that certain witnesses who had known them longest and best be called to speak on their behalf; and asked that spectral evidence not be allowed in the trials as it was not legal evidence, saying “…that the Testimony of witches, or such as are afflicted, as is supposed, by witches may not be improved to condemn us, without other Legal evidence concurring, we hope the Honoured Court & Jury will be soe tender of the lives of such, as we are who have for many years Lived under the unblemished reputation of Christianity, as not to condemne them without a fayre and equall hearing of what may be sayd for us, as well as against us.” The petition did not help much. Mary Eastey was tried on September 9, 1692. It is not known why Sarah was not scheduled for trial at that time.

The testimony against Mary was mostly stories from the girls about being afflicted by her specter and testimony from the girls’ relatives, such as Edward Putnam, describing how the girls appeared to be afflicted. Other people testified as well about interactions with Mary that they attributed to witchcraft, as is shown by this deposition of Samuel Smith below.

|

Trial Deposition of Samuel Smith,

Trial of Mary Easty, 1692

Click to make bigger. |

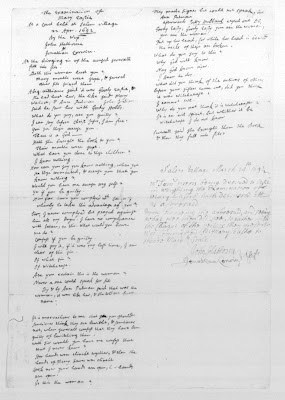

Transcription of deposition of Samuel Smith, who testified at Mary Easty’s trial to this incident:

The deposistion of Samuell Smith of Boxford about 25 yers who testifieth and saith that about five years sence I was one night att the house of Isaac Estick sen'r. of Topsfeild and I was as farr as I know to Rude in discorse and the above said Esticks wife said to me I would not have you be so rude in discorse for I might Rue it hereafter and as I was agoeing whom that night about a quarter of a mille from the said Esticks house by a stone wall I Received a little blow on my shoulder with I know not what and the stone wall rattleed very much which affrighted me my horse also was affrighted very much but I cannot give the reson of it.

Before her trial, Mary Easty was subject to another humiliation, in that a delegation of men and women from the town searched her nude body for a “witch mark” or “devil’s teat”, and purported to find one. Several people also had the courage to speak up on her behalf, such as John and Mary Arnold, and Thomas and Elizabeth Fosse, who submitted depositions and testified to how well behaved Mary Easty was when in jail. At the end of her trial, she was condemned to death by hanging.

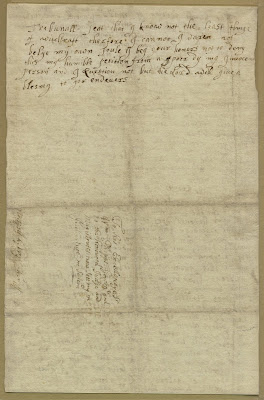

Before her execution, Mary Easty wrote another petition, which has been described: as ”one of the most moving historical documents to survive from the witch-hunt” by Francis Hill in Hunting for Witches; and in the book Puritans in America by Andrew Delbanco, it states “Hers is an expression of submission without servility. It is a statement of one person’s faith that New England can still be saved from itself.”

|

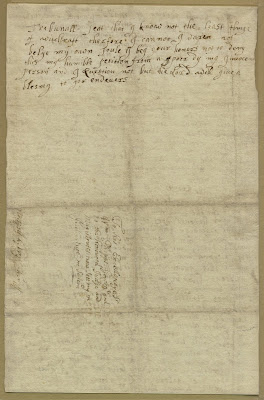

Mary Easty's Post-conviction Petition, 1692, front

Click to Make Bigger |

|

Mary Easty's Post-conviction Petition, 1692, back

Click to make bigger |

Transcription of Mary's post-conviction petition, pictured above:

“The humbl petition of mary Eastick unto his Excellency's S'r W'm Phipps to the honour'd Judge and Bench now Sitting in Judicature in Salem and the Reverend ministers humbly sheweth

That whereas your poor and humble petitioner being condemned to die Doe humbly begg of you to take it into your Judicious and pious considerations that your Poor and humble petitioner knowing my own Innocencye Blised be the Lord for it and seeing plainly the wiles and subtility of my accusers by my Selfe can not but Judge charitably of others that are going the same way of my selfe if the Lord stepps not mightily in. i was confined a whole month upon the same account that I am condemned now for and then cleared by the afflicted persons as some of your honours know and in two dayes time I was cryed out upon by them and have been confined and now am condemned to die the Lord above knows my Innocence then and Likewise does now as att the great day will be know to men and Angells -- I Petition to your honours not for my own life for I know I must die and my appointed time is sett but the Lord he knowes it is that if it be possible no more Innocent blood may be shed which undoubtidly cannot be Avoyded In the way and course you goe in. I question not but your honours does to the uttmost of your Powers in the discovery and detecting of witchcraft and witches and would not be gulty of Innocent blood for the world but by my own Innocency I know you are in this great work if it be his blessed you that no more Innocent blood be shed I would humbly begg of you that your honors would be plesed to examine theis Afflicted Persons strictly and keep them apart some time and Likewise to try some of these confesing wichis I being confident there is severall of them has belyed themselves and others as will appeare if not in this wor[l]d I am sure in the world to come whither I am now agoing and I Question not but youle see and alteration of thes things they my selfe and others having made a League with the Divel we cannot confesse I know and the Lord knowes as will shortly appeare they belye me and so I Question not but they doe others the Lord above who is the Searcher of all hearts knows that as I shall answer att the Tribunall seat that I know not the least thinge of witchcraft therfore I cannot I dare not belye my own soule I beg your honers not to deny this my humble petition from a poor dying Innocent person and I Question not but the Lord will give a blesing to yor endevers.”

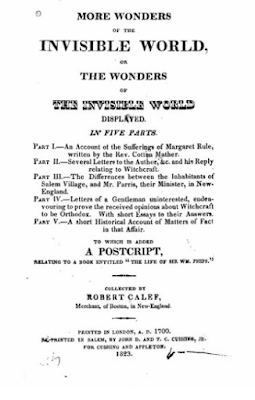

On September 22, 1692, Mary Easty and five others were hanged, one at a time, on a small hill near Calais Hill. Robert Calef, the author of More Wonders of the Invisible World, described her last moments: “Mary Easty, sister also to Rebecca Nurse, when she took her last farewell of her husband, children and friends, was, as is reported by them present, as serious, religious, distinct and affectionate as could well be exprest, drawing tears from the eyes of almost all present.”

|

More Wonders of the Invisible World, by Robert Calef, 1823

Click to make bigger |

It is not known where she is buried, although some believe that she was buried in an unmarked grave somewhere at the execution site.

It is possible that Mary’s petition had some effect on the minds of the leaders of the state as these were the last hangings of the witch trials. The last of the witch trials was on December 6, 1692, and by that time spectral evidence was no longer allowed. Only three people were convicted, and the governor granted reprieves so they were not hanged. Mary’s younger sister, Sarah Cloyce, was set free in January 1693 after her jail and court expenses were paid, when the grand jury in her case returned a verdict of “ignoramus,” or “I don’t know,” on each charge. The family quickly paid the bills and Sarah’s husband moved their family to Boston, away from her accusers.

After January 1693, no more accused witches were found guilty at trial. In May 1893 Gov. Phipps ordered all still held (150 people) released. On January 14, 1697, the General Court ordered a day of fasting and soul-searching for the tragedy of Salem. In 1702, the court declared the trials unlawful.

Mary’s husband, Isaac Easty, continued to fight for the restoration of Mary’s good name throughout the rest of his life. It took almost twenty years and several petitions to the legislature. In 1710, a committee was designated and met at Salem to consider the requests. Six Women of Salem, by Marilynne K. Roach, explained (and quoted from), that the committee reviewed a petition by Isaac Esty, age “about 82 years” who wrote of caring for his jailed wife Mary, saying that before her execution “my wife was near upon 5 months imprisoned all which time I provided maintenance for her at my own cost & charge, went constantly twice a week to provide for her what she needed.” Three of those weeks she was imprisoned in Boston “& I was constrained to be at the charge of transporting her to & fro.” He estimated his expenses “in time & money” worth 20 pounds sterling “besides my trouble & sorrow of heart in being deprived of her after such a manner which this world can never make me any compensation for.”

On Oct 17, 1711, the colony passed a bill restoring the rights and good names of some of those accused, stating that, “the several convictions, judgments, and attainders be, and hereby are, reversed, and declared to be null and void,” listing 22 people to whom it applied, including Mary Esty. Further, on Dec 17, 1711, Governor Dudley issued a warrant awarding Isaac 20 pounds sterling in compensation for the injustice of the 1692 verdict against Mary (equivalent to rent for a farm for a year in 1710 Massachusetts).

Isaac died about six months later on 11 June 1712, in Topsfield, Massachusetts.

It was not until 1957—more than 250 years later—that Massachusetts formally apologized for the events of 1692.

Our line of descent is as follows:

Isaac Estey, sr – Mary Towne

Isaac Estey, jr - Abigail Kimball

Richard Estey - Ruth Fisk

Zebulon Estey – Mary (Molly) Brown

David Currey, Sr – Dorothy Estey

George Currier – Eunice Phoebe Curry

George Butler Wilcox – Mary Jane Currier

Owen James Henn – Myrtle Wilcox

Owen Carl Henn – Anna Bennett

My parents

Me & my siblings

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

*Although I’m not going into detail as regards to the charges against, examination, and trial of Rebecca Nurse, or her execution, I note that Rebecca Nurse is the most famous of the three sisters and there are many books and articles written on her ordeal, including the play The Crucible by Arthur Miller. Additionally, her home survives as a Museum in Danvers, Massachusetts.

“England Births and Christenings, 1538-1975," database, FamilySearch; Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of Boston and Eastern Massachusetts, edited by William Richard Cutter, Vol 1 (1907), Vol. 2 (1908) and Vol. 3 (1908); A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April, 1692 by Deodat Lawson; (1692); “Mary Easty: the Witch’s daughter” by Rebecca Brooks, the History of Massachusetts’ blog, http://historyofmassachusetts.org/mary-easty-salem/ ; An American Family History blog, New England Families section, multiple pages, https://www.anamericanfamilyhistory.com/Navigation%20Indexes/New%20England.html ; https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3995254/Did-HALLUCINOGENS-spark-Salem-witch-trials-Experts-say-locals-eaten-bread-contaminated-fungus-LSD.html ; Currents of Malice: Mary Towne Eastey and Her Family in Salem Witchcraft by Persis MacMillen (P.E. Randall 1990); The Historical Collections of the Topsfield Historical Society, Vol. 14, Topsfield Historical Society, 1895 & Vol. 5 1899 & Vol 13 (1908); The Salem Witchcraft Papers, Verbatim Transcriptions of the Court Records In three volumes. Edited by Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum (Da Capo Press: New York, 1977.) Digital Edition, partially revised, corrected, and augmented by Benjamin C. Ray and Tara S. Wood, 2011, http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/texts/tei/swp, Mary Towne Esty Executed, September 22, 1692, http://salem.lib.virginia.edu/texts/tei/swp?div_id=n45 ; Hunting for Witches, by Frances Hill (Commonwealth Editions, an imprint of Applewood Books Inc., Carlisle Massachusetts, 2002); Six Women of Salem, by Marilynne K. Roach (MJF Books, New York. 2013.) The Wicked Court of Oyer and Terminar, http://people.ucls.uchicago.edu/~snekros/The%20Salem%20Colonial%20Current%202015/Oyer_and_Terminer.htm ; More Wonder of the Invisible World by Robert Calef, (printed in London 1700; reprinted in Salem by Cushing and Appleton 1823); The Puritans in America: a Narrative Anthology, by Andrew Delbanco (Harvard University Press. 2009); https://eh.net/encyclopedia/money-in-the-american-colonies./