My eighth great-grandfather was the oldest son of George

Harland and Elizabeth Duck, who I wrote about in January. He was born in the

Parish of Donaghcloney, County Down, Ireland. He was only eight years old when

his parents brought their family to the Pennsylvania colony in 1687. He had

eight younger siblings, the first three of which were also born in Ireland and

made the long journey to America with Ezekiel, his parents, and his uncle

Michael. For a listing of his sisters and brothers, please see the post on his father,

HERE.

A word about the dating used in this post before I continue

with the story. Before 1752

England and its colonies used the Julian Calendar, in which the first day of

the new year was March 25, and not the Gregorian Calendar (used today) in which

the first day of the new year is January 1. While the Quakers followed the

calendar commonly used by England, the Quakers designate months by numbers,

such that in the Julian calendar First month (or 1st mo. or 1)

was March. In writing dates in this essay that occur before 1752, I’ll state

what the date would be in today’s calendar and then, in parentheses, I’ll

include the date as I found it in the source used. [For a more in-depth

explanation of the Julian calendar transition to the Gregorian calendar, and Quaker

calendar see my post, Dating Induced

Headaches for the Family Historian: Julian, Gregorian, and Quaker Calendars.] Now on with the story of Ezekiel Harlan!

The main Irish ports from which ships sailed to William

Penn’s new Colony were Cork and Waterford. Although while vessels did sail

directly from those Irish ports, more often people took passage in ships which

sailed from Whitehaven, Liverpool, or Bristol, in England, which then stopped

at the Irish ports for passengers and cargo on the way. Philadelphia was the

main port of entry in America from Ireland, but many settlers landed at Newcastle,

on the Delaware River, and some at points in Maryland and Virginia.

The voyage from Ireland to the American colonies was a long

one, ranging from six weeks to three months depending on the weather and sea conditions. Ships were often driven far off course by contrary

winds and carried as far south as the West Indies. Additionally, dangerous

diseases, such as smallpox, frequently occurred, and many passengers died at

sea. George Harland and his wife Elizabeth (Duck) saw this new land as such a

new hope and opportunity that they chose to risk their young family, children

aged 4 to 8 years, in the hold of one of these ships for the long voyage to

Pennsylvania. The Harlans landed and settled in Newcastle (and dropped the

final “d” from their last name). Newcastle was then the largest city in the

lower three counties of Pennsylvania (which later became the state of

Delaware).

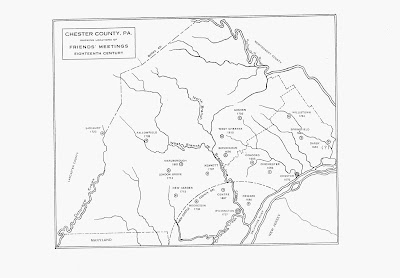

The first monthly meeting of friends in Pennsylvania

occurred in January 1681/2, five or six years before the Harlan family arrived,

thus the monthly meetings were well established when the family arrived. The

congregations of the Quaker meetings

already in Pennsylvania, especially the Philadelphia monthly meeting,

took special care of new immigrant Friends, welcoming them and advising them as

to where to settle, and often giving needed financial assistance, especially in

the payment of passage money, lending the new immigrants the money to pay the

bill the ships master charged to bring them to the colony, or buying out their

debt and taking them into service to work out their redemption. Once the immigrants

chose their land and secured title, the family would quickly move to their

chosen land so that their efforts in settlement will be well underway by the

time winter season began.

|

| The Landing of William Penn, by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930), depicting Penn's arrival at New Castle. In the Public Domain |

The Harlans initially settled on the west side of

Brandywine Creek, in the Christiana Hundred in Newcastle when Ezekiel was eight

or nine years old. The Christiana Hundred was one of the original Hundreds

created in 1682 and was named for the Christiana River that flows along its

southern boundary. A Hundred was an old English term for a portion of land,

like a County, was governed by a particular administrative or legal body. As

they were joining an already existing community, there were neighbors within a

reasonable distance to help and to provide more security than going further

inland by themselves. In the summer they attended the Newark meeting at

Valentine Hollingsworth’s house and, in the winter, because travel was treacherous,

they were allowed to hold meetings in the homes of their own community.

The whole family would have worked together to clear the forest

on their land to build a house. The first dwelling built by new immigrants to

the land was often a log cabin built from the trees they felled in order to

make the clearing in which to build the cabin. It was built of long logs placed

horizontally upon one another and notched together at the corners. The spaces

between the lots were filled in or kinked with stones or wedges of wood and

then plastered over with mortar or clay. The roof was covered with boards or

all shingles, either pinned by wood wooden pins or held in place by weight

timbers. A huge stone fireplace and chimney were built into one side of the

house to be used for cooking and heat. The English and Irish Quakers made their

log houses square not rectangular. As a family became more settled, and

survived the first winter, with crops harvested and re-planted, they added a

second floor. As they became more prosperous, the families would also build a

larger and more comfortable in addition to the house of brick or stone. A log house built, about 25 years later, in

1715, by Ezekiel’s younger brother Joshua still stands in Kennett Township,

Chester County, PA and is on the National Register of Historic Places. See the

picture below of Joshua’s house.

George Harlan moved his family about ten miles up the creek

further into Pennsylvania to Kennett Township in Chester County Pennsylvania in

1698 after buying 470 acres of land up there. Ezekiel was 19 at the time of

that move. The move would’ve been done with packhorses as there were no real

roads and a wagon would not make it through the forest, even along the creek

bank. The women and children and farm and household effects were loaded on the

packhorses, with the men traveling on foot, leading the horses and driving

their animal herds and flocks along before them. Again, they cleared land and

built a new home.

In the summer months George and his sons, including Ezekial,

were busy clearing and planting their land, and keeping their livestock. In

winter, if it was too cold or stormy for outside work, the male members of the

family would do such tasks indoors as making shoes for the family, repairing

horse tack, heating iron over the fire and berating it into farming or

household implements, and making household furniture and utensils. The women of

the household were even busier than the men. They would help the men in the

fields and in caring for the animals, but also did the cooking for the family,

washed dishes and clothes, made butter, made candles and soap and clothes, sewed

quilts, picked, carded, and spun wool and flax, knit, worked in the kitchen

garden, and had babies and cared for the children.

The produce and handicrafts of the farm were carried to

Philadelphia, Chester, or Newcastle, on horseback to be sold in markets or

fairs or exchanged for goods the household could not make themselves. They also

met and socialized with other Quakers on these trips. Despite the difficulty in travel the Friends

visited with each other regularly at harvests and huskings, barn and house

raisings, weddings and funerals, and at the twice weekly meetings on First-day

and Fifth-day. Quakers also met for quarterly and yearly business meetings that

brought in Friends from distant areas, which led to more socializing. The

Quarterly Meetings lasted for several days.

The Yearly Meeting for the Harlans’ area of Pennsylvania and Delaware,

as well as parts of New Jersey and Maryland, was held in Philadelphia for a week

or more each year.

The twice weekly Meetings were very important in a Quaker’s

life for worship and quiet socializing. At the meeting, the congregation sat on

hard, unpainted, un-cushioned benches, with women on one side and the men on

the other. After some moments of silent worship, from the raised seats in the

gallery facing the body of the meeting [congregation] where the ministers and

elders sat, a minister would stand and give a spiritual message. Often the

speaker was a travelling friend from England, Ireland, or other distant places.

In 1700, when Ezekiel was 21 years of age, he married Mary

Bezer (in the below record, Mary Bazer), by ceremony of Friends at the Concord Monthly Meeting in what is now

Delaware County Pennsylvania. Her family had come to the colony in 1683 when

she was only 1-year-old, settling in the area of that Meeting.

|

| Ezekial Harlan & Mary Bazer, Marriage Intention, 13 Jan 1700 (the 13th of the 11th month 1700) Minutes of Concord Monthly Meeting, Delaware PA |

Quakers required that marriage took place within the auspices

of the meeting; it was not something to engage in lightly or quickly. Companionship

and friendship were viewed as the proper base of a marriage. Romance was not

condemned but was conditioned upon a shared devotion to God. Men and women

chose their own spouses after months of corresponding and visiting. Parents

could not force their children into marriage. However, a man and woman were

required to have the approval of parents and their meetings to marry. To do this, the two first appeared before the

local women’s meeting. The records show the two chose the Concord Meeting that Mary

attended. The women’s meeting appointed

two people to meet with the couple separately to question them to ensure that

neither of them were already married, were non‐Quakers, or were otherwise unsuitable spouses.

Friends believed that the wife and husband should be supportive of the other’s

spiritual growth. Both partners were also expected to be capable of

contributing to their household and to raise their children as Quakers. If the

couple were found to be “clear of all entanglements” they were allowed to marry

according to the good order of Friends. The couple then had to appear at at

least two Men’s Meetings to declare their Intent to Marry before obtaining

approval to do so. These early Friends did not believe that a priest or

magistrate, or even a Quaker meeting, could perform a marriage. Only God could

do that. Marriages took place in a silent meeting where the man and woman rose

and affirmed their commitment to each other before God. Those present signed a

certificate witnessing that the marriage had actually taken place. Careful

records of witnesses were kept so courts would recognize the marriage and the

legitimacy of the children in it, to avoid later challenges to inheritance.

Ezekiel and Mary had only one child, William, my

seventh great-grandfather, who was born 1 Nov 1702 (9, 1, 1702) , died 22

October 1783, m. 14 Feb 1721 (12, 14, 1721). Unfortunately, Mary died shortly

after his birth, in 1702 in Christiana Hundred, New Castle, Pennsylvania.

Four years later, in 1705/6, Ezekiel married Ruth

Buffington in a ceremony of Friends. They had six children: Ezekiel, born July

19, 1707 (5, 19, 1707), died 1754, married Hannah Oborn, December 23, 1724 (10,

23, 1724); Mary, born June 12, 1709 (4, 12, 1709), died June 7, 1750 (4, 7,

1750), married Daniel Webb, November 28, 1727 (9, 28, 1727); Elizabeth, born

July 19, 1713, died ?, married William White, August 8, 1728 (6, 8, 1728);

Joseph, born August 14, 1721, died ?, married Hannah Roberts May 21, 1740 (3,

21, 1740); Ruth, born March 11, 1723 (1, 11, 1723), died ?, married Daniel

Leonard, May 28, 1740 (3, 28, 1740); and Benjamin, born October 7, 1729, died

October 1752 (8 Mo. 1752), at sea, unmarried.

Ezekiel and Ruth lived in Kennett in Chester County, on

property directly north of the Old Kennett Meetinghouse. The Old Kennett

Monthly Meetinghouse was built in 1710 by Ezekiel Harlan, on land deeded from

William Penn. The bicentennial history for the old Kennett meetinghouse states

that he “must have” conveyed the land for the meetinghouse, but the deed had

been lost. Ezekiel was described in a few sources as a farmer and a land

speculator. He dealt in lands throughout Chester County and adjoining counties.

He was appointed constable for the Township in 1706. In 1715, he was the

heaviest taxpayer in the Township, paying 12 shillings and sixpence, or

approximately six days wages for a skilled tradesman. 12 shillings and six pence

appear to be about double what most of the other people listed in the record

paid that year.

I lost him for about fifteen years after that. But in 1731,

he went to England, regarding what most sources described as “tradition holds

was business in connection with his father’s estate.” Before he left for

England, in an abundance of caution, he drafted his will. This was a tradition before

any long sea voyage. He survived the sea-crossing to England, but while there,

he contracted smallpox and died, at age 51, on 15 June 1731 (15 of 4 mo. 1731).

He was buried two days later near Bunnhill Fields, in Devonshire, England.

|

| The Will of Ezekiel Harlan, signed 14 Nov 1730. Probated 31 Jan 1732. (found in PA Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993, Collection on Ancestry.com) |

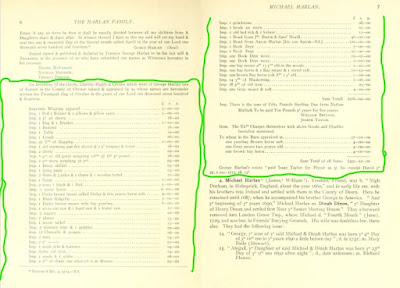

The Will of Ezekiel Harlan (transcription)

In the name of God Amen. I Ezekiel Harlan of the County of

Chester in the province of pennsivania in America Yeoman being in reasonable health

of body and of perfect mind and memory Thanks be to God for the same and being

about to take a voyage into old England and Calling to mind the uncertainty of

this life for the settling of my Temporal affairs I do make and ordain this my

last Will and Testament in manner and form following that is to say first

committing my soul to God I will order and appoint my boddy to be buried in a Decent

matter at ye Discretion of my Executrix hereinafter mentioned and Touching such

Worldly Estate and Substance were with God has Blessed me I give and appoint

and bequeath to my son William Harlan the sum of five Shillings and to my son

Ezekiel Harlan the sum of five shillings and my daughter Mary the wife of

Daniel Webb the sum of five Shillings and to my daughter Elizabeth the wife of

William White the sum of five Shillings and my sons Joseph and Benjamin Harlan

and to their heirs and assigns forever I Give and Bequeath Five hundred acres

of land to be equally divided between them share and share alike that is to say

250 acres each to be laid out at the direction of my executrix hereinafter

named which said Five hundred acres of land is to be part and parcell of the Tact

of Land which I now Dwell upon and to my daughter Ruth Harlan the sum of Fifty

pounds Current money of pennsilvania or the value in goods at the market price

and in any case any of my last mentioned three children viz Joseph, Benja, and

Ruth should happen to Dye before they attain the age of Twenty one yeares or

marry then and it is my will that the share or shares of each Child or Children

so dying shall be Equally Divided between the survivor or survivors of them and

my Executrix Share and Share alike.

Item I give and Bequeath unto my Dear and well Beloved wife

Ruth Harlan the remaining part or parcel of my plantation or tract of land on

which I now dwell after the said Five hundred acres is laid out to my two sons

Joseph and Benjamin in the manner aforesaid Together with all my personall Estate

of what kind or sort soever in order the better to Enable her to pay and

satisfy all my just Debts and funeral expenses and towards bringing up

maintaining and Educating of my children during their minority and lastly do a

ordain constitute and appoint my dear and well beloved wife Ruth Harlan soul

executrix of this my last will and Testament here by Revoking and making void

all other and Former Will or Wills heretofore made or published by me.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal

this Fourteenth day of November in the year of our Lord God one thousand seven

hundred and Thirty.

Signed Sealed Ezekiel

Harlan. (Seal)

and published in the

Presence of

Joseph Robinson.

William Webb Junior

Wm Henderson.

An inventory of Ezekiel Harlan’s goods, filed January,

1/31/32, and signed by Joseph Gibbons and James Taylor, places the value of his

worldly effects at the time of his death at 208 pounds 17 shillings. Appraised on

February 1, 1743/44, and signed by Jno. Marshall, Benjamin Taylor and Samuel

Sellars, the amount of the estate which passed to his widow, Ruth, amounted to

182 pounds, 19 shillings, six cents. In the report of the Executrix filed on 5

May 1734 by Ezekiel’s widow, Ruth Harlan, she listed 37 people to whom money

was paid in the administration of the will. Ruth outlived Ezekiel by about twelve years. She died before 2 Feb 1743, which is when her will was probated.

The Will of Ruth Harlan (transcription)

Be it known to all men by these presents that I Ruth Harlan

of Kennett in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and forty-three

being sick & weak of body but of sound and perfect Disposing mind &

memory do make and ordain this my Last Will & Testament in manner and form

following that is to say first and principally when it shall have pleased

Almighty God to call my Soul to his mercy that my Boddy be Decently interred at

the Discretion of my Executors hereinafter named, and in the next place my will

mind an order is that all my just Debts and funeral expenses shall be paid and

discharged as soon as possible after my decease And after all my Just Debts and

funeral expenses are paid and discharged I do devise and bequeath unto my son

Ezekiel Harlan of West Marlborough in the said county and province the sum of Five

shillings to be paid to him or his assigns within one year after my decease.

Also I Devise and Bequeath unto my son Joseph Harlan of Kennett aforesaid the

sum of Five shillings to be paid under him or his assigns within one year after

my decease and also I Give and Bequeath unto my son Benjamin Harlan the sum of Five

shillings to be paid under him when he shall have arrived at the age of 21

years. Allso I Devis and bequeath unto my daughter Mary Webb & relict of

Daniell Webb Late of Kennett deceased the sum of Five pounds to be paid to her

or her heirs within one year after my decease. Allso I devise & Bequeath

unto my said daughter Mary Webb my sattin Gown to be delivered to her

immediately after my decease. Allso I devise and bequeath unto my daughter

Elizabeth White my Gown made of wool & worsted and my quilted Petticoat and

the Remainder of my wearing apparrall l I give Devise and Bequeath to my

daughter Ruth the wife of Daniel Leonard. Allso I get devise and bequeath the wooll

of my sheepe to be Equally divided between my two Daughters namely the

above-mentioned Elizabeth White the wife of William White and Ruth the wife of

Daniel Leonard. Allso I give devise and Bequeath unto my said daughter Ruth

Leonard the seventeen acres of Land by me reserved out of the Lands left me by

my husband Ezekiel Harlan Deceased & the House where I now Dwell & allso

the orchard and a piece of Meadow called the Calf Passture & a piece of Wood

Land at the Discretion of my executors so that the whole of the land in orchard

Meadow Ground Woodland &c shall not exceed Seventeen acres To hold to the said

Ruth Leonard during her Natural Life and after her decease I Give devise and

bequeath the seventeen acres of Land & Premises above-mentioned to my son

Benjamin & his heirs and Assigns forever, and the Remainder or Overplus of

my Estate after my Just Debts funeral expenses & the above mentioned Legacies

are paid and discharged I do Will in order to be Equally Divided between my two

above mentioned Daughters, namely, Elizabeth White and Ruth Leonard.

Also my will mind and desire is that my son Benjamin be put

to apprentice in a Convenient Time after my Decease to my Brotherinlaw Charles

Turner of Birmingham untill he be the age of Twenty years to learn the Trade

and art of Cordwainer & I do hereby constitute and appoint my son Ezekiel

Harlan above-mentioned to be the sole Executor of this my Last Will and

testament and my soninlaw* William Harlan of West Marlborough aforesaid to be Overseer

& Trustee for the performance thereof but without the power of admintr

except in case it shall so happen my son Ezekiel shall die before he shall have

accomplished and fulfilled the performance of his Administration & Executorship

to this my Last Will & Testament.

And I do hereby revoke Disallow & make void all and all

manner & other and former Wills & Testaments by me heretofore made,

hereby ratifying and confirming and declaring this and no other to be my Last Will

& Testament.

In witness whereof together with the publication hereof I

have hereunto set my hand and seal the day in the year first above written.

JOSEPH TAYLOR. Her mark.

Witnesses: John Walker. RuTH X Harlan. (Seal)

Thomas Worrall. Mark

proved February 2, 1733/4

*"soninlaw" is now called stepson

---------------