|

| United Empire Loyalist Flag, Public Domain |

It is, perhaps, a good thing that much of my early research on my paternal side of the family had to do with Canadian history (since many of the Scotts-rooted and Irish-rooted branches of the family tree emigrated through Canada and the pre-Canadian British colonies in the north). Because I've read so many blogs written by Canadian genea-bloggers, and histories written by Canadian authors, I know how special it is, from the Canadian perspective, to have a U. E. Loyalist in the family. As an American, I knew it would probably not politic to post this on July 4, because to have a U. E. Loyalist in the family means that they fought on the "other side” of the Revolutionary war and that would disappoint some of my family.

Joshua Currey, my fifth great-grandfather, on my Dad’s side, was born in about December 1741 to Richard Currey, Jr (4 Nov 1709- 20 Mar 1806) and Elizabeth Jones (about Dec 1711-14 Feb 1778) in Cortlandtown, Westchester County New York.

In about 1730, Richard Currey, Jr., after marrying Elizabeth Jones, mounted both of them on a single horse, and with all their effects, rode northward into the deep forests of northern Westchester County, which was still occupied by the Algonquins, and bought land in the Peekskill Creek Valley in the Cortlandt Manor (Westchester County, NY, which was then divided into huge tracts of land called Manors [with one owner] and Patents [owned by multiple people]), a few miles back from the Hudson River. At that point, he carved out a home and farm, eventually becoming a large landowner, and raised his family there. Richard and Elizabeth, my sixth great-grandparents, had at least ten children. I’ve seen some people’s trees with more children listed for them but I’m going with the ones listed in his will as I haven’t been able to confirm any others at this point: Sarah Currey (1736-1770, m. John Jones), my fifth great-grandfather Joshua Currey, Stephen Currey (1742-1830, m. Frances Moore), Jemima Currey (1744-1825, m. Elisha Horton, Sr), Richard Currey (1750-1835, m. Sarah Ferris), Phoebe Currey (??-??, m. John Sherwood), Elizabeth Currey (??-??, m. Robert Wright), Mary Currey (??- 1806, m. John Smith), Martha Currey (??-??, m. ? Sherwood) and Rachel Currey (? - before 1806, m. William Lane).

|

| New York State (now rather than then, unfortunately) with Westchester County in red By User:Rcsprinter123 [CC BY-SA 3.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons |

In a short biographical article on one of his descendants, amongst the section that talks about his family history it reports that ”when Joshua grew two years of understanding, he married”. I don’t know what that means in terms of how old he was, but he married Eunice Travis, born in about 1750, daughter of Justus Meade Travis (abt 1728-abt 1793); I’ve been unable to find out who her mother is. Joshua owned 144 acres and farmed near his father’s lands in the Manor of Cordtland. He and Eunice had a beautiful house on that land and had six children born there: Richard Currey (1765-1857, m. Rebecca Dykeman), my 4th great-grandfather David Currey, Sr (1767-1827, m. Dorothy Estey, Gilbert Currey (1771-1857, m. Sarah Oakley), and Eunice Phoebe Currey (1780-1845, m. Moses Dykeman).

In the years after 1771, the local political climate had become tense. There were more Loyalists New York than in any other colony. It broke down to about 50 percent Patriots and 50 percent Loyalists, although historians agree that both sides were more American than British. It’s just that the Patriots did not see a way of reconciling with Great Britain and stood for independence as a separate country, and Loyalists stood for the recognition of law as against rebellion in any form, for the unity of the Empire as opposed to a separate independent existence of the colonies, and for monarchy instead of Republicanism. The Loyalists wanted the freedoms colonists had grown to enjoy across the ocean from Great Britain and reform of the oppressive taxation without representation system currently in place, but they were conservatives in their approach as to how to achieve this. History is written from the point of view of the victor: because the Patriots won the war fought against the British from 1775 to 1783, it is known as the Revolutionary War, the American War for Independence, or Our Rebellion. Had the British won, the war would likely have become known as the North American continent’s first Civil War.

In August 1775, New York Patriots determined that as the Loyalists were so numerous, regulations must be adopted to control them or the whole cause was in jeopardy and made a resolution that anyone found guilty of furnishing supplies to the British Army and Navy was to be disarmed and to forfeit to New York double the value of the articles they supplied and were to be imprisoned for three months after the forfeiture was paid. A second offense would be followed by banishment from the colony for seven years. By 1776, Loyalists were being arrested for arming to support the British or aiding the enemy in any way; harboring or associating with Tories (another name for Loyalists); recruiting soldiers; refusing to muster with local Patriot forces; corresponding with Loyalists or with the British; refusing to sign a document saying that they were Patriots; denouncing or refusing to obey congresses and committees; writing or speaking against the American cause; rejecting continental money; refusing to give up arms; drinking the king’s health; inciting or taking part in Tory plots and riots; being royal officers; and for trying to remain neutral. Mere suspicion was sufficient cause for seizure and imprisonment. All the property of those who adhered to the King or helped him in his war against the states was made liable to seizure.

Unlike his father and brothers, who supported the colonists, Joshua Currey sided with the British. This put his life in danger. At one time he had to hide under the floor of his house to escape the anger of the revolutionists, and his son David was nearly killed by them by being buried in a sandpit. He was also fined a number of times for failing to attend musters of the local Patriot militia. He was driven from his home and family, and forced to live in the woods, “skulking about, watching to see when it might be safe to return home.”

In Westchester County, the farms, stock, crops, and furniture of Loyalists were seized and sold before December 6, 1776. By March 1777, Joshua had joined the British Army, he and his family leaving home in the dead of night and traveling 300 miles to the nearest British camp, where they found protection from Sir William Howe, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in North America. Joshua first served with Major-General Tryon, commander of British Forces on Long Island, NY, and subsequently served with a section of the Loyal American Regiment (or LAR, which was primarily made up of Loyalists from Westchester County and lower Dutchess County) known as the Guides and Pioneers, under Colonel Beverly Robinson which put him at the forefront of any action against Patriot forces. In the Guides and Pioneers, Joshua was promoted to lieutenant.

|

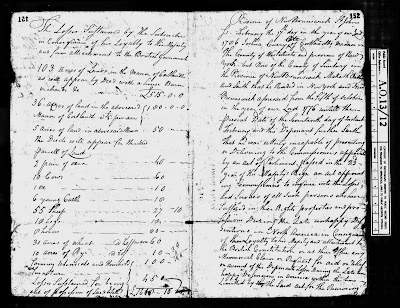

| First Page of Memorial Of Joshua Currey, claim for reparations Photo taken by H.C., used with permission Click to make bigger |

His family had presumed him dead as they had not seen him until the end of the war. After his service with the LAR, he worked as a refugee farmer behind the British lines, in Morrisania, in what is now the Bronx. The war officially ended with the treaty of peace and separation in 1783. The English government tried to provide for their Loyalist subjects in America through the terms of the Treaty. The fourth article of the Treaty stated that creditors on each side should "meet with no lawful impediment” to recover all their debts in sterling money. The fifth article held that the Congress of the United States should recommend to the states the restoration of the rights and possessions of ”real British subjects” and of Loyalists who had not born arms against their countrymen. All other Loyalists were given the liberty to go into any state within 12 months to adjust their affairs and to recover their confiscated property upon paying the purchasers the sale price. The sixth article stated that no future confiscation should be made, that imprisoned Loyalists should be released, and no further persecutions should be permitted. The Congress sent the “recommendations” to the states but stated that they had no power to enforce them. The state of New York felt no obligation to restore Tory lands and to allow the returning Loyalists to be treated as fellow citizens. The provisions of the Treaty were rejected and the New York legislature declared that the forfeited and taken property should not be returned since England had offered no compensation for property which had been destroyed. Loyalists who returned under the treaty of peace were insulted, tarred and feathered, beaten, whipped and otherwise assaulted. The New York legislature also revoked the voting rights of any who had served under the British finding them guilty of treason. Therefore, most New York Loyalists chose to become exiles.

|

| In the public domain. Click to make bigger |

The British Army could see the way things were going, and the officers petitioned the Crown to allow for ships and supplies to resettle their loyal subjects, now refugees, in other British colonies. Over the next six months, 30,000 Loyalist refugees would take ship to Nova Scotia, with almost half going to the St. John River Valley area. Because of the huge influx of citizens, the new province of New Brunswick was separated from Nova Scotia in 1784. (For the most part civilian refugees were sent to Nova Scotia and former military refugees were sent to what became New Brunswick, along the strategically valuable Bay of Fundy.) Each family received two tents, and one and a half blankets per person; each man received 4 yards of woolen cloth, 7 yards of linen cloth, two pairs of shoes, two pairs of stockings, one pair of mittens; each woman received 3 yards of woolen cloth, six charts of linen, one pair of shoes, one pair of stockings, and one pair of mittens; each child over the age of 10, received 3 yards of woolen cloth, 6 yards of linen, one pair of stockings, and one pair of mittens; each child under 10, received 1 ½ yards of wool and 3 yards of linen. They were also given provisions for the trip to Nova Scotia and were to be given one year‘s provisions thereafter. The weekly ration consisted of 1 pound of flour per person, half a pound of meat (either beef or pork), a tiny amount of butter, a half a pound of oatmeal a week and a half of pound of pease per week and a little rice. Some areas had molasses and vinegar but they were rare. The settlers could supplement the provisions with hunting and fishing.

|

| Map of New Brunswick |

|

| The Arrival of the Loyalists in the public domain Click to make bigger |

In the fall of 1783, Joshua and his family evacuated with the British forces to the St. John River Valley and received a land grant upriver around Gagetown, New Brunswick. My 4th great-grandfather David Currey, Sr., was 16 at the time the family arrived at St. John’s (then Nova Scotia).

Joshua later presented a claim to the commission for inquiring into the Losses, Services, and Claims, of the American Loyalists. He was one of only 500 New Brunswick Loyalists to do so. Joshua stated that he had lost 103 acres in the Manor of Cortlandt for which he paid 400 pounds was worth 500 pounds now, 36 acres of woodland also in Cortlandt Manor which he had cleared and values now at 5 pounds per acre, and 5 acres adjacent which he was once offered 10 pounds per acre for. He also had the following confiscated and sold by the NY government: two oxen (40 pounds), six cows (60), an ox, (10) young six young cattle (10), 55 sheep (27), 18 hogs (10), eight horses (00), 30 acres of wheat (40 pounds per acre… 60), 10 acres of rye (at 20… 10; farming utensils and household (100 pounds); furniture (450 pounds); losses sustained for being out of possession of said estate for nine years (1610.10 pounds). No one received all that they requested on their claims; the average payout was one-third to one-half of value asked. I don’t know what Joshua received.

|

| Second and Third Pages of Memorial Of Joshua Currey, claim for reparations Photo taken by H.C., used with permission Click to make bigger |

They spent this first year in or near St. John as they had arrived just before winter. The late fall was wet and cold, and the first snow fell on November 2nd – 6 inches! Those who had arrived earlier had started building log cabins and wood sheds for shelter for the winter, but many of those who arrived in late fall had to spend the winter in pitched tents covered in spruce branches for insulation. It snowed a lot that winter, which turned out to be a benefit as the six feet of snow around the tents helped keep out the bitter cold. Many families slept in shifts throughout the night to keep a fire going to keep the family from freezing (and not burn down the tent). Many women and children died that winter. Men hunted bear and moose to feed their families as the delivery of the promised provisions was erratic, at best. As spring came on, and the two-foot thick ice on the river and bay thawed, they also fished, and trapped pigeons, and ate fiddlehead ferns and the leaves of the trees. One account said the people cheered when the first schooner arrived carrying cornmeal and rye.

For Joshua and his family, as for many, their new life was a hard life, and a step backward from the comfort of their New York estate to the hard work of prior generations. In the spring they moved upriver to lands near Gagetown. He and his sons had to clear the land they bought in the parishes of Gagetown & Canning as it was a dense forest, chopping down trees and lopping off limbs to make the long trunks easier to transport; and the stumps had to be burned or dug out before the family could plow and plant crops. All this was done by people working together by hand because no one had been able to bring teams of oxen or horses on the ships. Potatoes and beans were planted amongst the burned stumps the first year and did well.

|

| A Loyalist Family Starts Anew In the public domain. Click to make bigger. |

The British government eventually sent seeds “for garden and farm”. By July 1784, the British government distributed an ax, a hoe, a spade, and a plow to every two families; a whipsaw and a crosscut saw to every fourth family; and a set of carpenter’s tools to every five families. Later, a cow was given to every two families, and one bull per neighborhood.

The first homes the new settlers built were simple log cabins consisting of round logs, from 5 to 20 feet in length, laid horizontally over each other, and bound at the corners, with the seams packed with moss and clay. Chimneys were built of stacked stone set in clay. A few rafters would be put up to hold a roof which was made of bark tied to thin poles laid across and tied to the roof frame. It might have had a framed floor or it might have been dirt initially. If they put in windows, they were small. Later, in 1789, Joshua built his family a large frame and brick home.

After life settled down, Joshua and Eunice had two more children in St. John County: Daniel Travis Curry (1785-22 June 1867; m. Elizabeth “Betsy” Scribner) and Joshua Curry, Jr (?? – aft 1802). As the initial hardships disappeared, the people became comfortable and prosperous, for the land was fertile, and the early sacrifices made for loyalty to King and Empire became more of something to brag about than to complain about.

In November 1789, Lord Dorchester requested the council at Quebec “to put a mark of honor upon the families who adhered to the unity of the empire and joined the Royal Standard in America before the Treaty of Separation in the year 1783”. The council concurred. Accordingly, all Loyalists who fit that description “were to be distinguished by the letters U.E. [United Empire] affixed to their names, alluding to their great principle, the unity of the Empire.” A Registry of these U.E. Loyalists was ordered to be kept and for twenty years names were added to this list. Joshua Currey is on the list.

Joshua Currey died at age 60 on 20 September 1802. He must have realized he was dying because that is also the day he drafted his will. He was survived by his wife and all of his children. In his will, he said, in pertinent part (with legalese translated into English, in brackets, where unnecessarily convoluted),

“I give and bequeath to Eunus, my dearly beloved wife the whole of my property both real and personal during such time as shall be and continue my widow and no Longer [if she remarried, the property was to be distributed as if she were dead].

“I also give and bequeath to my son Richard Currey the sum of 5 pounds and to my son David the sum of 2 pounds ten shillings and to my son Gilbert the sum of 1 pound 5 shillings and to my son Joshua the sum of 25 pounds to be in the care of Richard and David Currey. And five shillings I gave to my daughter Phebe Dickman and all that remain of my estate to my son Daniel Currey. [He named his] dearly beloved sons Richard Currey and David Currey to be my … executors [and states they are to be paid from the estate in the amount the law directs].“

[Note: One pound sterling in 1802 is equivalent to $98.76 in U.S. dollars in 2018.]

He was buried in Chase Cemetery, Gagetown, New Brunswick, Canada.

|

| Tombstone of Joshua Currey Photo taken by H.C., used with permission. Click to make bigger |

________________________

Sorry about the weird spacing folks. I tried to fix it several times but it won't get better, and twice it got worse, I've given up.

________________________

The wills of Richard Currey, and Joshua Currey (Found at Ancestry.com); Old Sands Street Methodist Episcopal Church, of Brooklyn NY, an illustrated Centennial record, historical and biographical, by the Rev. Edwin Warriner, corresponding secretary of the New York conference historical Society (New York: Phillips & Hunt, 805 Broadway. 1885), p. 441; Joshua Currey’s Claim for Reparations, The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; American Loyalist Claims, Series I; Class: AO 13; Piece: 098; The Journal of the Rev. Silas Constant, Pastor of the Presbyterian Church at Yorktown NY, With Some of the records of the Church and a List of His marriages, 1784-1825, Together with notes on the Nelsons, Van Cortlandt, Warren, and some other families Mentioned in the Journal by Silas Constant, Emily Warren Roebling, (Printed for Private Circulation by J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, 1903), p. 116 (https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=L0kVAAAAYAAJ&pg=GBS.PA116) ; https://earlyamericanists.com/2014/02/18/was-the-american-revolution-a-civil-war/ ; https://www.historyextra.com/period/georgian/facts-american-war-of-independence-declaration-battle-yorktown-george-iii-colonies/ ; The King’s Men: Loyalist military units in the American Revolution, Hudson Valley and New York City Loyalists: http://www.nyhistory.net/drums/kingsmen_02.htm /; http://www.royalprovincial.com/military/rhist/g&p/gphist.htm; United Empire Loyalists, Second Report of the Bureau of Archives for the Province of Ontario, part 1 by Alexander Fraser, Provincial Archivist, 1904; http://www.uelac.org/ ; http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Info/Loyalist_list.php?letter=c ; http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Info/detail.php?letter=c&line=863 ; http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Trails/2012/Loyalist-Trails-2012.php?issue=201223 ; History of New Brunswick, by Peter Fish (as originally published in 1825, with a few additional explanatory note, reprinted jointly by The Government of New Brunswick & William Shives Fisher, grandson of the author, under the auspices of the New Brunswick Historical Society, St. John, N.B. 1921); “Evacuation Day”, 1783 Its Many Stirring Events: With Recollections of Capt. John Van Arsdale, by James Riker (New York 1883); The Loyalists of New Brunswick, by Esther Clark Wright (Lancelot Press, Windsor N.S. 1955; A Biographical Sketch of Lemuel Allen Currey and Biographical Sketch of John Zebulon Currie, Cyclopedia of Canadian biography, being chiefly men of the time. A collection of persons distinguished in professional and political life; leaders in the commerce and industry of Canada, and successful pioneers, by George MacLean Rose, (Toronto: Rose Publishing Company. 1888.); Biographical Sketch of Frank A. Curry. Biographical history of Westchester County New York, illustrated. Volume II (The Lewis Publishing Company. Chicago: 1889, pp. 974-977.); New Brunswick Loyalists of the War of the American Revolution, New York Genealogical and Biographical Society Record, Vol 35-36 1904-1905, Oct., p.277-281; Planters, Paupers, and Pioneers, English Settlers in Atlantic Canada, by Lucille H. Campey (The Dundurn Group, Toronto CA, 2010); Tories: Fighting for the King in America’s First Civil War by Thomas B. Allen (Harper Collins E-books, 2010; Loyalism in New York during the American Revolution by Alexander Clarence Flick, Ph.D (New York, Columbia University Press, 1901); Loyalist Regiments of the American Revolutionary War 1775-1783, by Stuart Salmon, Ph.D. Dissertation, 2009; and https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm.